Photos by Igo Eusebio

Clothes define the times. It reflects a culture’s beliefs and norms, and a civilization’s progress. As time runs, fashion evolves with it.

Gino Gonzales, a Gawad Urian 2018 awardee for Best Production Design and co-author of the fashion history book, “Fashionable Filipinas,” was at MINT College last February 7 to talk about the history and art of our national dress, or what we know now as the Terno.

Gonzales is a scenographer, i.e. a production designer, who graduated from New York University. He took part in theater and film productions locally and abroad, and won a major award at Gawad Urian 2018 for his production design for the film, “Ang Larawan.” His eye for detail to recreate the aesthetics needed for staged productions led him to his current advocacy of highlighting local Philippine fashion and reliving the rich history and art of creating our women’s national costume.

He has curated over a hundred photos to be able to illustrate the evolution of women’s fashion in the Philippines. Some of these could be found at @fashionable_filipinas Instagram account, which he moderates. Together with co-author Mark Higgins, co-director of Slim’s Fashion and Arts School, they retraced the roots of our women’s national costume, starting from pre-colonial Philippines up to the 60s.

Gonzales began his Terno presentation by showing a series of colorful illustrations by Spanish-era historians to depict how the natives of the archipelago dressed before they came.

“Women before the Spanish conquest walked freely with their bosoms bared, wearing only a huge and long cloth tucked at their hips, to cover their intimates,” he explained. “However, that didn’t sit well to the standards of decency by the Spanish colonizers.” He also added that only those at the upper ranks of society could afford to wear tops and accessorize themselves with gold.

After the Philippines was conquered by the Spaniards, the natives were forced to adapt the Western dress code, and began wearing separate layers of clothing.

The baro’t saya, or if worn by affluent women, the traje de mestiza, consisted of the camison or inner blouse as first layer of cover, topped with baro or the blouse with long and billowy sleeves, and then covered with a panuelo or a starched cloth acting as a shawl to fully cover their once-bare bosoms. They also started to wear ankle-length skirts.

In his book, he quoted that our national dress was the most adaptive of the Western trends, yet it’s modified in a way that’s distinctively ours. “It was through the Galleon trade that our local fashion adapted the Western trends, particularly Parisian and English.”

“The more intricate the embroidery and the more volume added to the sleeves signified a woman’s high social standing back then,” he shares. “At times, it will also dictate if a woman is eligible to attend school,” he added.

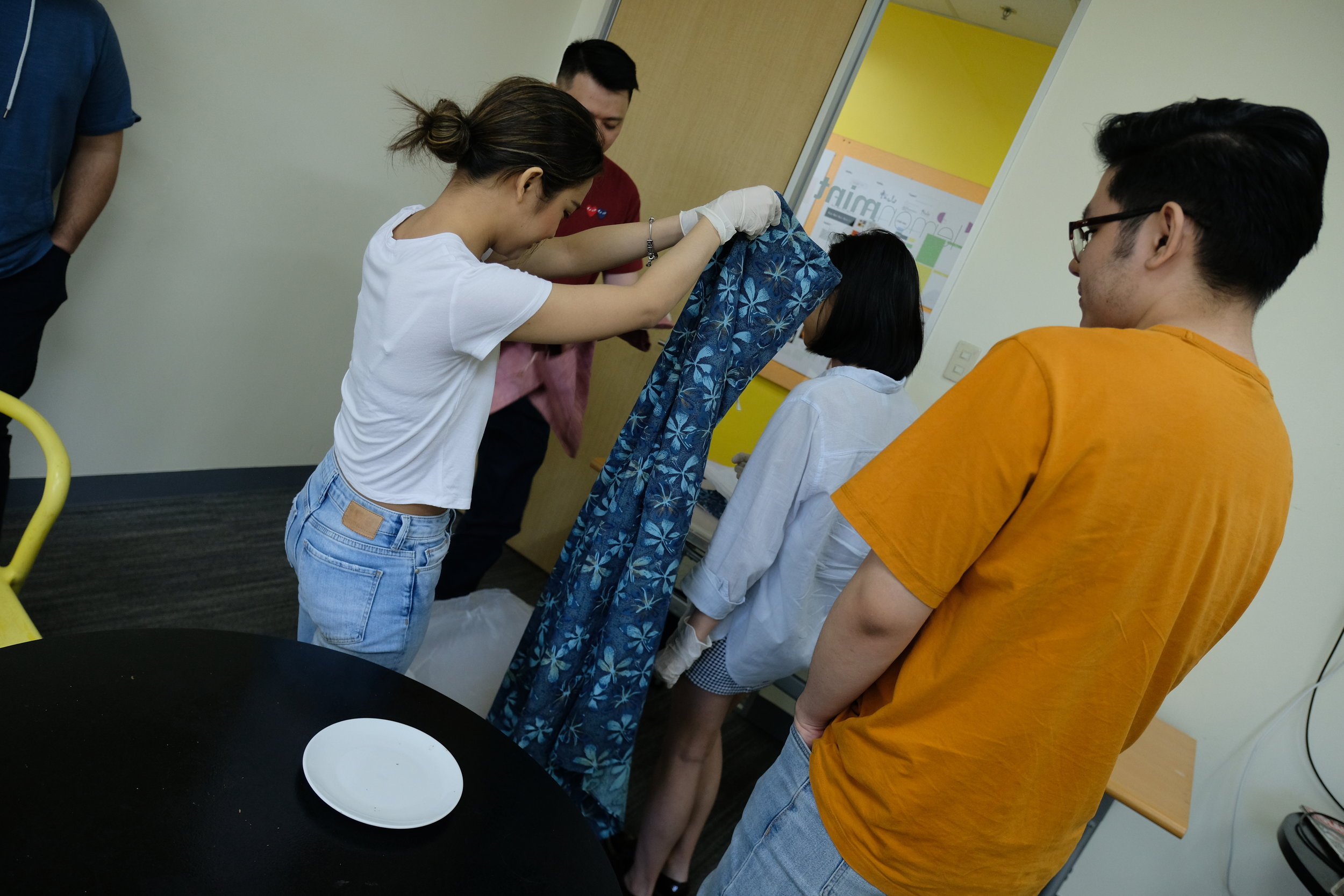

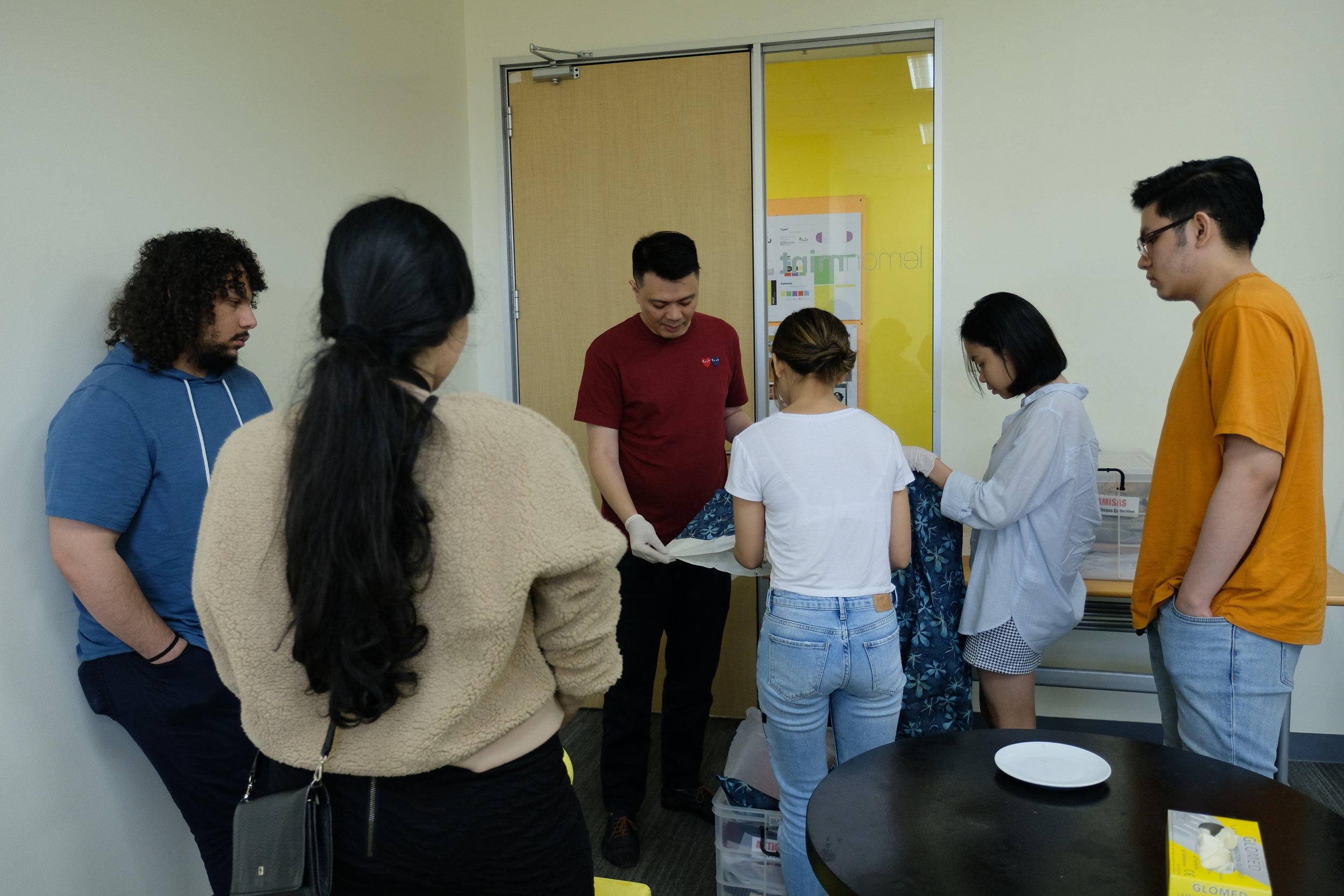

As the Western styles progressed to shed layers and became more body-fitting, the baro’t saya also followed suit. The panuelo was eventually dropped and the voluminous, billowy sleeves were modified to appear as stiffly arched sleeves we now know of. In the latter part of his lecture, he also showed to MINT students how to properly construct the modern terno’s stiff butterfly sleeves.

For MINT Fashion student Aleksa Meily, she understood that “patience, precision, and consideration” must be at the forefront of making the terno, so as to preserve its distinct Philippine style.

For Meily, her most important takeaway from Gonzales’ lecture was that fashion is culture. “Every creation, no matter how many modifications it went through, will always reflect the creator’s culture,” she said. W

For more information about MINT’s Fashion Program, visit us at http://bit.ly/MINTSchoolOfFashion and you can also check out MINT School of Fashion’s Instagram at @mintfashionschool